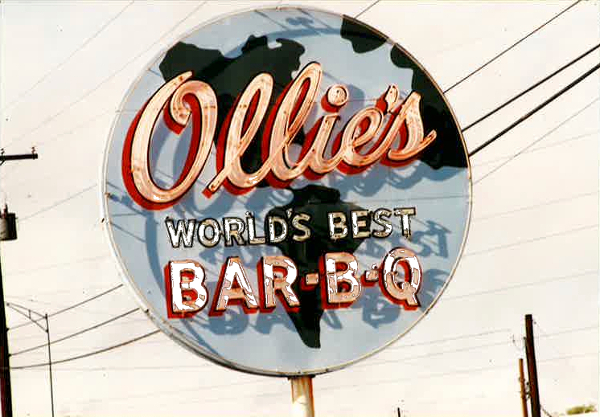

The distinctive sign outside Ollie’s Barbecue/Photo courtesy Ollie McClung Junior

One of the enduring images of the Civil Rights Movement is of black protesters being pulled away from lunch counters. Fifty years ago this Sunday a U.S. Supreme Court ruling effectively ended segregation in restaurants. That case came from Birmingham.

In the Jim Crow South, restaurants were segregated but some white establishments would serve black customers on a take out basis. Washington Booker grew up in Birmingham and was a teenager in the early 1960s. He remembers the routine.

“Some restaurants would let you come in. Go up to the counter and order,” Booker said. “You had to have a certain kind of posture. You had to just stand there. Couldn’t just be looking around. And then when your sandwich came, you took it and you left.”

Booker says the restrictions in restaurants or the downtown department store lunch counter stung.

“You may not remember all the other discrimination but the fact that you couldn’t go into Newberry’s and sit at that counter and get you a banana split kind of bothered you,” said Booker.

Congress banned such discrimination in the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Many restaurants complied, but not all.

Ollie McClung Junior and his dad owned Ollie’s Barbecue at that time. A Birmingham landmark founded by his grandfather, McClung says it was the kind of place where white plumbers and electricians sat next to white doctors and bank presidents. Bible verses hung on the walls. McClung says the staff could take on a lunch crowd that often stretched out the door.

“We had wonderful waitresses, many of them were with us 30 and 40 years,” said McClung. “They never wrote anything down. That was one of the highlights of people coming in the place.”

The majority of Ollie’s employees were black and McClung says they had some regular black customers. But as was the norm when segregation was the law, they were only served take out. When the Civil Rights Act went into effect McClung and his dad were concerned seating blacks would drive away white patrons. So they sued.

“Most people are going to say the heart of the matter was the rights of black people. The real heart of the matter was, now wait a minute, the federal government can’t come in and tell us what to do. We’re a local business,” said McClung.

At the time southern politicians often used a states rights defense to justify segregation. A three-judge panel in Birmingham sided with the family initially. But on appeal the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously against them. Southern politicians were up in arms about a decision they felt was unconstitutional.

“But I think among constitutional scholars there was virtually no doubt whatsoever that the Congress had the power to do this,” said Richard Cortner, a retired University of Arizona political science professor who wrote a book about the case.

He says Ollie’s Barbecue was a local business. But the court says Congress can regulate local actions that in aggregate would have an effect on interstate commerce.

Ollie McClung Junior says he and his father were disappointed by the ruling. Fifty years later he feels much the same.

“Whether to have or not have segregation, obviously that has changed. But the decision at the time, no?” said McClung. “Still think they got it wrong.”

But they obeyed the ruling.

McClung says the day after the decision a group of black civil rights leaders came into the restaurant.

“But my waitresses, black ladies who were waitresses, they were kind of like stand offish,” said McClung. “I said, go ahead and serve them like anybody else.”

He says integration didn’t hurt the restaurant, nor did it really increase their black clientele. That doesn’t surprise Nathan Turner Junior. He grew up nearby and doesn’t remember any black people going there even after the court case.

“Just the fact that Ollie’s pushed it that far, to take it to the Supreme Court, it left a bad taste, pun intended, in the mouths of a lot of black people in Birmingham,” said Turner.

McClung closed Ollie’s Barbecue in 2001 and sold the sauce recipe. The sauce is still on grocery story shelves around Birmingham. It’s a reminder of the battle for the chance to eat that barbecue on equal terms.