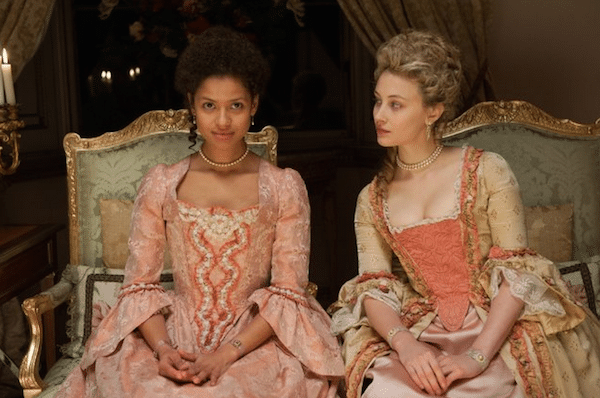

The film Belle explores the story of a young mixed race woman who is the daughter of a Royal Navy Admiral. She’s raised in a white aristocratic family in 18th century England.

The film, inspired by a true story, shows the challenges the main character grapples with as she comes to terms with her skin color.

The story hit home for our guest blogger Javacia Harris Bowser, who explores the complexity of the term “colorism” in her latest blog post for WBHM. She started off by telling WBHM’s Sarah Delia why the main character of the film Belle resonated with her so much.

There is a scene in the movie Belle that brings me to tears.

The movie, though fictional, was inspired by the true story of Dido Elizabeth Belle. Last month I finally made it to a local theater to see the movie with one of my best friends.

Belle, as she’s called in the movie, was the illegitimate mixed-race daughter of the nephew of William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, who was later Lord Chief Justice of England in the 1700s. At his nephew’s request, Murray takes in Belle and raises her as a member of his family, despite her brown skin.

But, because of her skin color, Belle can’t sit at the dinner table when the family has guests. In one scene, Belle stares in the mirror and begins to violently rub her face and chest — as if she can wipe, wish, and will her color away.

I can relate to this heart-wrenching moment.

Though I have obviously never lived in a world in which the enslavement of or even the discrimination against black people is supported by law, I have spent many days hating the color of my skin. Unlike Belle, however, it was not white people who made me feel this way, but people of my own race.

Discrimination based on skin color is often referred to as colorism. With colorism, lighter-skinned people are usually favored, sometimes considered smarter, kinder, and more attractive. Colorism is not solely an American issue, as it is a problem in Africa, Southeast Asia, East Asia, India, and Latin America as well. Colorism can exist between different races or within the same race. That’s how I have experienced it most.

As a child I didn’t know the word colorism. But when I overheard one of my uncles jokingly say that if his children had been born dark-skinned he would have smothered them in the hospital, I did know this so-called joke wasn’t funny.

When I was a child, my skin tone was much lighter than it is today. But just as a Caucasian child’s hair color might change as he or she gets older, so did the color of my skin. I grew darker each year. I didn’t think this was a big deal until people started to offer me unsolicited comfort, assuring me that I was “still pretty” in spite of my dark brown skin.

As an adult, when I started signing up for half-marathons, some of my family members told me I needed to stop. Running outside in the sun was only making me darker, they’d say.

Black men flirting with me would often say they’d never met a dark-skinned woman as pretty as I, actually thinking that I would consider that a compliment. And an ex-boyfriend, trying to explain such comments, once told me that light-skinned black women are more attractive because they’re more feminine.

When I started wearing my hair in its naturally curly state, people would look at the soft ringlets flowing down my back and ask how a dark-skinned person could have such “good hair.” It didn’t seem right, they’d say.

But none of these things hurt as much as overhearing two of my black female students at the fine arts school where I teach arguing with each other over whether they were the color of caramel or chocolate. They even began to poll passers-by in the hallway. They counted each vote for “caramel” as a win.

I stopped and tried to convince them that they were beautiful regardless of their skin color. But I knew nothing I could say could erase the experiences that made them think otherwise.

I recalled all this while watching Belle. I wont spoil the ending, but I will say that Belle grows to no longer hate the color of her skin. She becomes unashamed of her mother’s heritage and rejects anyone who believes she should be. Her confidence eventually sways the thoughts of powerful men like her great uncle.

I left the theater with a tear-stained face but with a heart full of hope. I left believing that self-love is a revolutionary act. Whether a person is disparaged because of race, skin color, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or body type, when marginalized people love themselves in spite of a society telling them they should not, they are true rebels indeed. And this self-love can often be the first steps toward systemic change or cultural shifts.

African Americans in the South loved themselves enough to know they deserved better than what “separate but equal” dogma would allow them. Through the civil rights movement of the 1960s, they dismantled the laws of Jim Crow.

I too wish to practice this transformative love — I will love myself enough to know that my skin color is not a flaw. And my hope is that my confidence will be contagious to the teen girls in my life.

I will love myself enough to run freely in the sun, with my curls dancing in the wind.

Javacia Harris Bowser is an educator and freelance writer in Birmingham. Javacia is the founder of See Jane Write, an organization for local women writers, and she blogs about her life as a “southern fried feminist” at The Writeous Babe Project.