Alabama Versus the Volcano

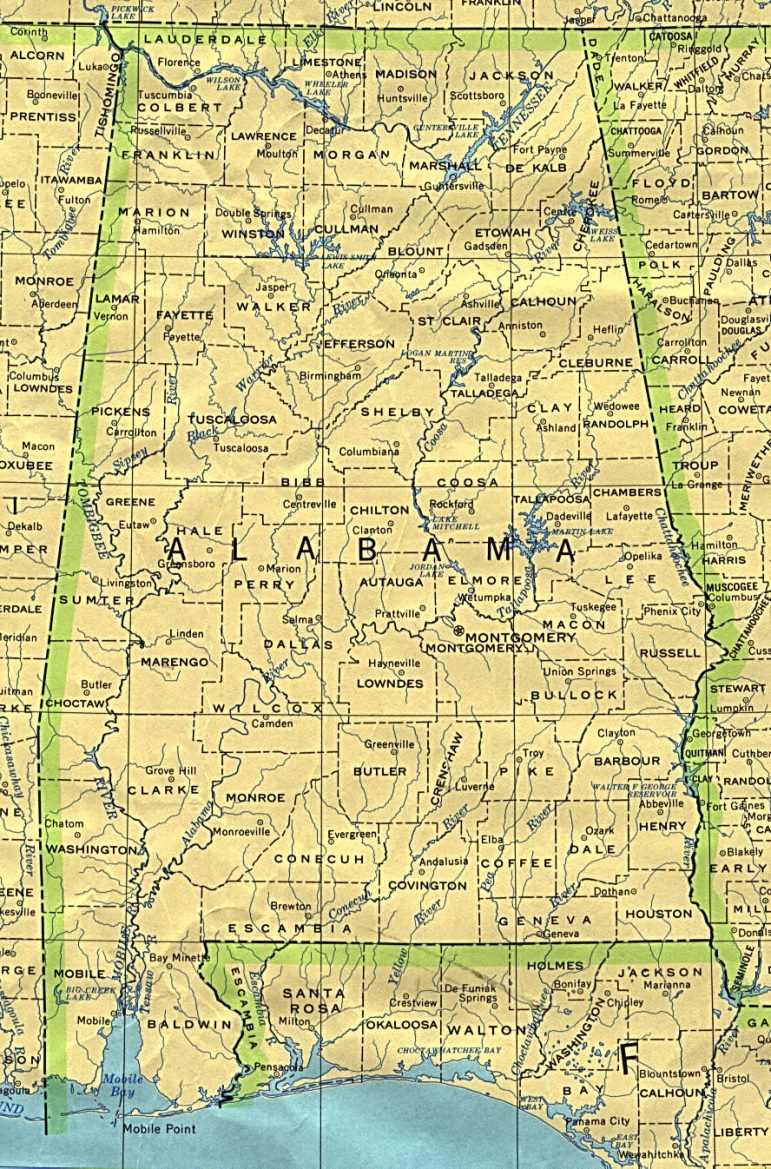

Climate change is forcing some Alabamians to consider a move. Coastal areas and islands like Dauphin are losing land as the sea rises, flooding is more frequent, and hurricanes could be more dangerous than ever. But for one couple, natural disasters are no deterrent. They’ve left the Yellow Hammer state for a new life in one of the riskiest places on earth.

Near the end of Route 30 on Hawaii’s big island the stars look down on a stark expanse of black lava – no trees, no bushes, just miles of rolling black rock. Kent Napper, a 52-year-old native of Vernon, Alabama, keeps watch as several hundred tourists arrive. Napper helps people find their way to the county’s viewing area, about 3 miles from Pu’u’o’o – a volcanic crater that’s been oozing lava for the last 30 years. They want to see molten rock – glowing red and sending up clouds of steam as it flows slowly into the sea, but if they want to feel the heat, visitors must hike those three miles. The ground is uneven, and Napper warns people to go only with a licensed guide who has permission to cross private property:

“From out at the end of the road, on the lava field, it’s very dangerous – broken legs, injuries like that. There are a lot of dangers associated, of course, with the hot lava, and also around the ocean entry there’s different fumes that are very dangerous.”

Pu’u’o’o is also a danger to her neighbors. In 1990, a whole subdivision was wiped out – 160 houses buried under 40 feet of lava. But that hasn’t stopped Napper, his partner Nancy Lowe, who hails from Hurley, Mississippi, and about 40 other people from building on the old site of Kalapana Gardens.

“When we just came out here to look at the lot on the lava, the wind and the sun and the ocean views and the lava views – there was no question. This was the property for us. It captured my heart. I loved it out here. The rebirth, the regrowth of it – the pioneer spirit of coming out somewhere different.”

And a steady trade wind cools the sparsely settled neighborhood to keep the air clean and cool. Napper and Lowe didn’t need a building permit, and the land was cheap by Hawaiian standards. While other lots might sell for over a million dollars, home sites here cost as little as $5,000. They do pay property taxes, and they have to maintain their own unpaved road, but there’s no charge for water or electricity.

“The bill does not arrive. That’s exactly right. We like that.”

Instead, the couple catches rainwater, which is plentiful, and generates power from the sun and wind.

” We have solar panels for electricity which runs our computers, our TV, our refrigerator, lights, and we cook and heat our hot water with propane. It’s very nice, very comfortable. High speed Internet, any convenience that we would have in town.”

They don’t have insurance, and they know their small, two-story wooden house, surrounded by decks, could be destroyed should the volcano send lava their way.

” I do think about it, and back in March, the last house in a community up on the hill was lost, and watching videos of that – it really kind of hit home, but I mean we have a beautiful life here, and, I think it’s worth it. There is not a lot of success in trying to fight it, and the fire department would not be here spraying water on it. They’re just going to let it burn. We are not necessarily worried, but we are aware. We are aware that the volcano is in charge. We are here as long as the volcano lets us stay here.”

And they’re consoled by the fact that lava moves slowly — giving them time to pack up and drive away – something southern tornadoes don’t do, and they’re glad to be far from the Gulf Coast where they’ve seen how dangerous hurricanes can be.

~ Reporting by Sandy Hausman