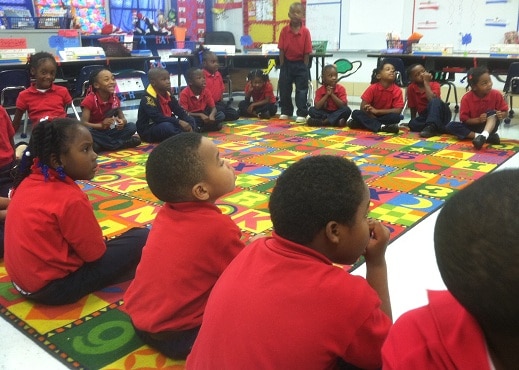

The positive reinforcement that is a mainstay of classes at Mobile’s George Hall Elementary mirrors

the praise coming in from around the country. At least 95 percent of students here consistently score at or

above grade level in math and reading. Educators from other districts come to observe and learn. It’s

been a national Blue Ribbon school, a state Torchbearer School, and according to tech giant Intel, it

has the best elementary math instruction in the United States.

But it wasn’t always like this. Before 2004, its chronic “low-performing” status, behavior problems, and

failure to teach the most basic skills were the norm. Things were so bad federal funding was in jeopardy.

Principal Terri Tomlinson says demographics were sometimes used as excuses: 99 percent of George Hall students are black and poor. She adds,

“Most of the homes are substandard. The average education of our parents is somewhere

between eighth grade and less than high-school graduation. Most of our parents are single moms, or

grandmothers, raising children. And it’s, it really is … this is generational poverty.”

But in 2004, the district decided on a plan. It cleared out almost all the staff, brought in Tomlinson, and recruited highly

qualified teachers. The new staff had to have a strong work ethic and a belief that all kids can learn at a

high level. Teachers got $4,000 signing bonuses and performance bonuses of up to that amount, but if the applicants even mentioned the money in their interviews, they were quickly rejected.

And of course, all this was just the beginning. Even after neighborhood families watched staff clean and paint the school all

summer, there was mistrust. According to Title One specialist and writing support teacher Melissa Mitchell, “They just saw us as change, and, a lot of times, in generational poverty especially, change is

not well received. It’s scary. And they didn’t know our intentions.”

It was also unnerving for staff. Looking back, she says, “The first quarter of school was … was very scary and I didn’t anticipate the anger that was

going to come toward us. I was verbally accosted, constantly.”

She says parents were reacting to an overhaul of school procedures — basic things including locking side

doors during the day. But Principal Tomlinson says the mistrust had a deeper source, too:

“We were a predominantly white staff and a white principal who came into a black school

with a predominantly black staff and a black principal, and it was … it was hard for it not to be racial.

And there were threats.”

Including a knife stuck in the ground on school property. And, Tomlinson says, “We were egged, they took dead fish and rubbed it all over the bricks, and shrimp — oh it was awful.”

All this points to an oft-forgotten fact: Though George Hall is a model now, the turnaround was hard and painful.

The district tried to transform four other failing schools that year. None were as successful as George

Hall. And community mistrust was just one complication.

According to Danny Goodwin, head of the Mobile

branch of the Alabama Education Association, “Teachers were hurt. They were being blamed for problems which were societal. There was

no effort to find out whether anybody was doing a good job, a poor job, a wonderful job. It was just, ‘All

a’ y’all go.'”

So there were hard feelings, and contested staff transfers, too. Goodwin still criticizes the way the transformation was handled, including school board members very publicly questioning the competence of the former George Hall staff. But that’s mainly fallen by the wayside, even for Goodwin and the AEA.

“[George Hall is] an example of what can be done,” he says. “They have done a wonderful job there, and I

want everybody to understand we’re very proud of their accomplishments.”

The community around the school now supports George Hall, too. So, how exactly did the staff achieve

success so undeniable that no one wants to argue with it? For more on that, check Part Five, the conclusion of our series on Turnaround Schools.