Plaintiffs in Lynch vs. Alabama Property Tax Case to Appeal Recent Ruling

Unequal Local School Funding in Black Belt, Other Rural Areas at Issue

The plaintiffs in Lynch vs. Alabama, a complex court battle with implications for school funding across this state, are set to file an appeal of a federal judge’s Oct. 21 ruling against them by the end of this week.

“It’s still an uphill battle, but we just have to convince some judges in Atlanta of our case,” plaintiff’s attorney James Blacksher said today. After meeting with the plaintiffs from Sumter County and then those from Lawrence County, Blacksher and the rest of his team have the go-ahead to file the paperwork with the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals required by Monday Nov. 21 at the latest.

Last month U.S. District Judge Lynwood Smith excoriated Alabama’s property tax system but ultimately rebuffed the plaintiffs who’d alleged the system is unconstitutionally racist. He issued an 854-page opinion, notable for both its length and its passionate denunciation of the tax code, that seemed poised to turn Alabama’s property tax system on its head. But in the end, though outraged by “unequal and inadequate public school funding,” Smith deferred to the will of the legislature, to the state’s Constitution, and to state Supreme Court precedent.

Alabama has the lowest property taxes in the nation, and provisions that protect farmers, timber owners, and other landowners bring in little local funding for school systems in rural areas. Homes, farms, and timberland are taxed at 10 percent of market value, but “current use” provisions mean property is assessed at its value as, say, productive farmland or timberland. That tends to come in much lower than that 10 percent assessment level would, which results in a lack of local revenue in districts with little developed real estate or commercial enterprise.

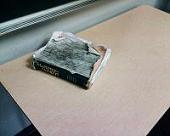

In 2008, parents of students in the two counties sued the state on behalf of their children. They said the property tax system deprives rural, mainly black districts of the funding needed for an education comparable to that in other parts of the state, and that the history of property taxation and school funding in Alabama is a continuous narrative of state-sanctioned racism. They cited dilapidated buildings, limited programs, and textbook shortages as evidence. But according to Judge Smith, a Clinton appointee, the plaintiffs did not prove that the effects of the lowest-in-the-country property taxes fall along racial lines.

“None of this is meant to say, however, that the court is satisfied as to either the quality or the equality of public education in this state,” he wrote, adding that the lack of adequate funding hinders the life prospects of rural students, black and white, and therefore Alabama’s long-term economic viability.

Six months after a four-week trial that included more than 700 exhibits, 1,000 pages of documents, and testimony from historians on Reconstruction, cotton farming, poll taxes, George Wallace, the Civil Rights Movement, desegregation, and busing, Smith delivered his unusually long opinion.

State Attorney General Luther Strange said Smith’s ruling, “confirms the State’s consistent position that Alabama’s property tax structure does not violate the United States Constitution. It is the prerogative of the citizens of Alabama, through their elected representatives, to structure a tax system in a manner that best serves their interests. The Office of Attorney General remains committed to defending and vindicating this important right whenever necessary.”

But attorney Blacksher described it differently:

“Judge Smith issued this exhaustive ruling, and then at the eleventh hour changed his mind. He had all these findings of fact that, when correct legal principles are applied, should find for the plaintiffs …. That will be our argument.”

Photo of farmland by Oakley Originals; photo of old textbook by CrazyTales562, courtesy of Flickr.