It’s Saturday morning in Homewood Park. Joel Jenkins is riding up and down tall ramps on his skateboard. Although he says he fractured his vertebrae a few years ago, he’s not about to quit.

“I mean, I get pain in it, but it’s bearable. I love doing it and everything. I mean. My Dad tried to get me to stop. How am I supposed to stop doing something I love?”

If you’ve ever gone eye-to-eye with a teenager, trying to get them to see the consequences of their actions, this scene is all too familiar. Are teenagers intentionally being reckless? Do they not even try to understand “this” causes “that”? Scientific research suggests that a young brain may not allow a teenager to fully appreciate the connection between actions and consequences.

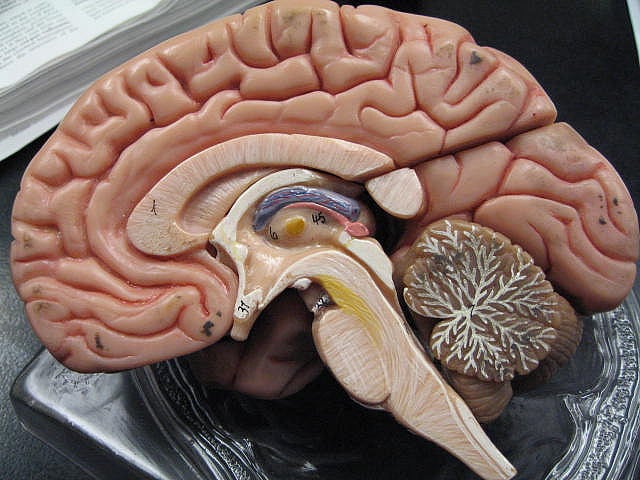

Every two years, for the last 17 years, a group of kids has been coming to a lab in Maryland to have their brains scanned by an MRI. The study, by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health, suggests teens have a long way to go to fully comprehend the consequences of risky behavior. The number of brain cells and their connections surge just before puberty. Through adolescence, however, cells and connections go through sort of a “use it or lose it” process.

“You see what’s called pruning.”

Joe Ackerson is director of pediatric neuropsychology at UAB.

“Which is a selective programmed cell death, which then makes that area more efficient in how it operates. So, it’s like the brain is preparing itself for another stage of growth with the prefrontal cortex, and then it kind of refines that process over the subsequent six, eight, ten years.

The prefrontal cortex is the CEO of the brain. It’s involved in things like planning, organizing-thinking logically. While the prefrontal cortex is still going through these changes, the lymphic system of the brain-that’s the emotional center-is more developed and advanced. It drives teens to seek things they want. In most teenage brains, since the two systems are not fully connected, they aren’t on the same page.

“So, you’re kind of like one of those old cars with a very large engine, but very weak brakes. And, so the impulse and the drive kind of overrides the capacity to stop and think and reflect and weigh, “Is this something I really want to do right now or not.”

Ackerson notes during this time of “storm and stress,” teenagers don’t intentionally look at adults as human pinball machines-enjoying pushing our buttons just to see us light up. There are other things afoot.

“They’re trying to assert their own identity, and as they’re formulating their own identity, they not just looking to their parents, now they’re looking to peers. They are far more likely to be influenced by popular culture, during these times. So, you can see a conflict of cultures and a conflict of values at this time.

This conflict of culture and values is causing some vigorous debate within the juvenile justice system. Joe Ackerson’s wife, Kimberly, specializes in forensic psychology. She evaluates juveniles to determine their mental state at the time of their crime, competence to stand trial, and whether they should be transferred to the adult judicial system.

“It’s extremely important to look at the child’s maturity and development to help understand why they may have committed this act. And, while our legal system really does not excuse behavior based on limited development, per se, I think we are remiss if we don’t take into consideration that these juveniles often commit acts as a result of physical maturity, or if you will, physical immaturity.”

Kimberly Ackerson says research on teen brain development is gaining traction among defense attorneys, prosecutors and judges. But, she says not everyone in the judicial system is onboard.

“I don’t see the equal trend of their being referred for evaluation and again, I think with the research showing so well, that these juveniles are not fully developed, that I think it’s even more important that these individuals be referred for evaluation, just so that the court can be assured that the juveniles are at a position where they can assist the attorneys, where they proceed to court and also to ensure that there was not something to help explain the offense, for which the juvenile is coming to court.”

Compounding the issue, Kimberly Ackerson says there’s an increase in juveniles with mental illness. Alabama doesn’t track these numbers, but a national study by the Virginia Policy Team found one in five juveniles in the court system have a serious mental disorder and Individual states have reported increasing rates.

“And, one of things that is happening actively within the field of psychology is a push for more community-based services that can work with juveniles, not only addressing issues of mental health, but also addressing issues like developmental immaturity and helping these children become more mature in more appropriate ways, and be able to handle the demands of society, which we know, of course are very demanding.”

Harvard psychiatrist Deborah Waber says all of this discussion on how a teen’s brain affects their capacity to think clearly and know right from wrong is very intriguing. But, she says, an underdeveloped brain is no excuse for criminal behavior.

“I think that’s not a sort of understanding of the brain that I would be happy with, because it sort of makes people think, well that’s just my brain, I have no free will. Well, free will is your brain. I think we have to be very careful about being too deterministic about brain science. Yes, it’s going to bias kids to be more impulsive than we would like them to be, when they’re adolescents, but that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t expect them to be able to make good decisions.”

University of Alabama criminologist Bob Sigler says many politicians agree with Waber.

“We have to get tough on crime, period, in that cycle between treatment and punishment, because people believe that people in the community want them to be tough on crime. You can take a look at the legislation that’s been coming out in a number of states. It’s almost not rational anymore. They’ve done everything reasonable, tightening up on crime, but some of the things they do are unreasonable.”

Research teams continue the difficult task of searching for links between specific traits of teen’s brains and their real-life decisions and behaviors. While some believe brain data is eventually going to support reduced legal culpability for adolescents, others like Deborah Weber, aren’t convinced.