TAKING ON TESTS: Atlanta School Students Still Recovering From Cheating Scandal

Atlanta’s infamous public school cheating scandal sent some educators to jail last year and forced the system to clean up its culture of pressure-driven testing. But after the educators were found guilty of changing tests answers and sentenced, thousands of innocent victims remained: school children.

Some students had academic deficiencies that were never discovered or addressed. And as the most recent graduates prepare now for college or careers, some Atlanta Public Schools continue programs to re-mediate and support though challenges still remain.

Lawyers pleaded for leniency, and a judge flailed his hands in disgust in the April 2015 sentencing of Atlanta educators, guilty of cheating to boost student test scores. That’s the way they got bonuses or, in many cases, held on to their jobs.

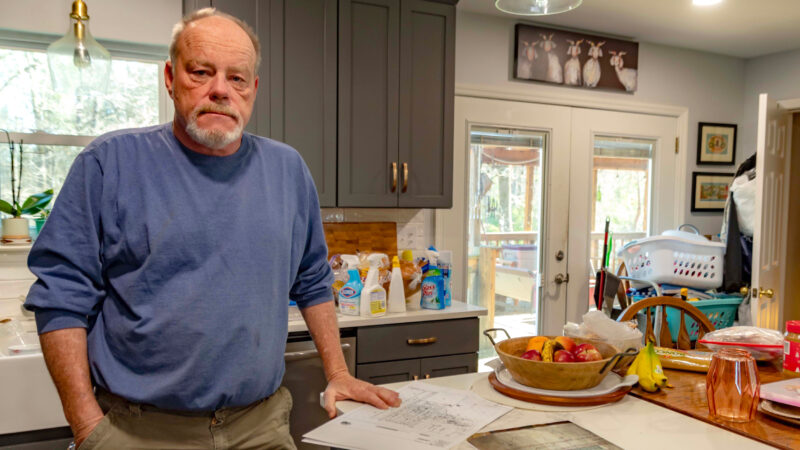

Educators had funding, job evaluations, and more tied to student performance on the Criterion Referenced Competency Test or CRCT. For Sandra Harper Gallashaw’s daughter, Shandreamer, the impact of the cheating scandal is real. Her daughter attended Parks Middle School — the one where the principal testified he orchestrated cheating to protect his job. After the scandal erupted, she says the school was unstable.

“They have removed so many teachers,” says Gallashaw. “It was said that when they removed 178 people that were involved in the scandal that we would have professional people to teach our children, but all they gave us was substitute teachers — people coming and going,” she continues.

When her daughter went to high school, Gallashaw says the stigma followed her.

“It’s been a struggle because when she first got to Carver — how the teacher treated her. They knew these children were from the cheating scandal,” says Gallashaw. “And she actually quoted one of her teachers saying they should have taught her that at Parks.”

Gallashaw says her daughter had a tough time in some high school classes. She wanted to go to Tuskegee University in Atlanta, but didn’t get accepted. Now she’s considering going to the Navy.

A recent study from Georgia State University backs up Gallashaw’s assumption. Dr. Tim Sass says his research shows students were permanently damaged by efforts made to make them look better on paper.

“It appears that having their scores manipulated in the past led to lower student achievement, particularly in language and reading,” says Sass. “The reduction achievement we found was on the order of somewhere between a quarter and a half year of typical student learning.”

His study found as many as 7,000 students were potentially harmed by the scandal, and about half of them are still in school. Dr. Alicia Hill, an administrator for one of the Atlanta Public Schools programs designed to help cheating scandal students, uses Sass’s data to help students through a program called Target 2021.

“The program is geared toward the students who are potentially affected by the CRCT erasure in 2009,” Hill says. “That’s our response to make sure we are providing students with our support throughout graduation or the time that they graduate to make sure that they’re college and career ready.”

Atlanta has tried a variety of academic recovery and remediation efforts in recent years. Sandra Gallashaw has had two daughters graduate from the school system, and said she has doubts about its efforts.

“They haven’t tried enough,” Gallashaw says. “Just Saturday School for the high school students. One day out of how many years these folks been cheating. Just one day? It’s a smack in the face.”

Hill acknowledges there are challenges and criticism.

“We have lots of challenges and skepticism and there will be criticism, but also success is knowing that as we are getting this off the ground and running. There are people who are saying ‘This is great. I’m glad you are doing something,’” Hill says.

The school system is spending $9 million to support students through programs like Communities in Schools, or CIS, headed by Frank Brown.

“We are actually case managing every one of these students and making sure that if they have needs that are academic in nature,” Brown says. “We are sending them to tutoring.”

Yet, he says, it takes more than just tutoring to serve and support the students who attended schools that were part of the cheating scandal.

“We bring an array of CIS services. That’s drop out prevention programming, anti-bullying campaign. AT&T wants to do career exploration. Anytime something like this happens and it has nationwide attention, there’s a sensitivity there,” he says. “Parents want to know what I can get my child to get them where they need to be academically and emotionally. How can we get control of this horrific situation that they had no control over.”

The last group of students potentially impacted by the cheating scandal is projected to graduate in 2021. And while the verdict for the educators has been decided, seven years after the scandal broke — the actual verdict for the students still is uncertain.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What’s your favorite thing about Alabama?

That's the question we put to those at our recent News and Brews community pop-ups at Hop City and Saturn in Birmingham.

Q&A: A former New Orleans police chief says it’s time the U.S. changes its marijuana policy

Ronal Serpas is one of 32 law enforcement leaders who signed a letter sent to President Biden in support of moving marijuana to a Schedule III drug.

How food stamps could play a key role in fixing Jackson’s broken water system

JXN Water's affordability plan aims to raise much-needed revenue while offering discounts to customers in need, but it is currently tied up in court.

Alabama mine cited for federal safety violations since home explosion led to grandfather’s death, grandson’s injuries

Following a home explosion that killed one and critically injured another, residents want to know more about the mine under their community. So far, their questions have largely gone unanswered.

Crawfish prices are finally dropping, but farmers and fishers are still struggling

Last year’s devastating drought in Louisiana killed off large crops of crawfish, leading to a tough season for farmers, fishers and seafood lovers.