Sewer Overflows Persist Despite Billions Spent

Every few weeks, Nelson Brooke drives through Jefferson County to check on the spots where the sewer overflows. Brooke is the head of the environmental group Black Warrior Riverkeeper.

At a stop, ten blocks west of downtown Birmingham, Brooke checks on Valley Creek. The water should be clear, but on this day, it looks more like broccoli soup.

“That kind of green-grey, milky cloudiness is a very common thing when you have sewage in water,” Brooke said.

He says it’s been this way for more than a decade. County officials say they don’t know where the sewage is coming from.

Later on his patrol, Brooke knocks on doors to see if residents know of sewage problems in their neighborhoods. Across the street, a young man calls out to ask if Brooke is lost.

“Do you know about sewer overflows?” Brooke asks the man. “Where sewage is coming out of manholes?”

Michael Alexander points to a slope in the street. “That’s right here,” he said. “When it rains on this street [sewage] comes out here here and here.”

Alexander, 37, has lived on this block since he was a kid. He says for nearly 30 years the sewer has been overflowing into the street.

“Every time it rains, the sewage comes up out of there and you can’t walk across [the road],” Alexander said. “You splash your car through there, you are going to have crap on your [tires]. You might have a tampon hanging off.”

Alexander makes a face. “The smell is terrible,” he said. “It’s like that for two blocks.”

Alexander says he and his neighbors have just learned to live with it.

A Long Running Problem

In 1993 local environmental groups sued Jefferson County which resulted in the Environmental Protection Agency, issuing a consent decree, requiring Jefferson County to comply with the Clean Water Act and stop dumping raw sewage into local rivers and streams. To fix the sewer problems, the county spent over three billion dollars. Except some of the money wasn’t spent on the sewers, it became embroiled in a corruption scandal that led to the county filing for bankruptcy in 2011. At the time it was largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history.

In some neighborhoods, sewer overflows continue today.

“Why did you not fix the sewer, when we gave you all of that billions of dollars?” said Shelia Tyson, a Birmingham city councilwoman for the neighborhoods where many of the sewer overflows occur.

Tyson says residents have complained to her of sewage backed up in their yards. They report bad smells, asthma, and skin rashes. Tyson worries raw sewage leaks are causing health problems and that public officials don’t seem to care.

“You know why? It hasn’t hit home yet. It hasn’t affected people with money,” Tyson said. “This is a poor person’s issue. It’s not in their community.”

The County’s Response

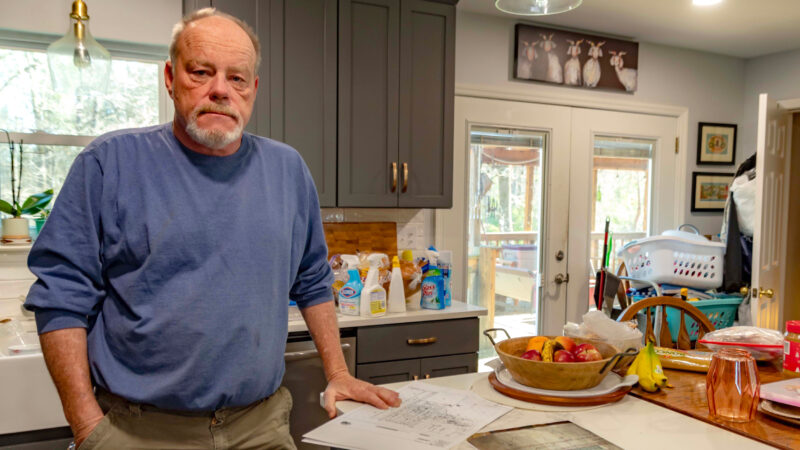

Director of Environmental Services for Jefferson County David Dennard says it’s not completely the county’s fault.

“Really all of the issues where we are having these recurring overflow areas happen in former municipal systems,” Dennard said. He explains the county took over Birmingham and other cities’ sewer systems, and as a result, it’s been playing catch-up with these overflows.

Dennard says the county has checked off two-thirds of the EPA’s orders in the consent decree and fixed 99 percent of the sewage overflows.

Dan Biles, Deputy County Manager for Infrastructure, says they fixed the biggest problems first, such as sewage flowing into the Cahaba Riiver. He says It’s not because it’s in a wealthier neighborhood, but because the problem was bigger.

“It doesn’t matter where it is, wherever [we] can spend the dollar to get the best bang for our buck,” Biles said. “Whether it’s Lincoln Ave or Fifth Ave or wherever, it’s about reducing [overflows] and making the most impact.”

Dennard has acknowledged that sewage has overflowed into the streets and creeks of southwest Birmingham for years, so that’s where they are focusing their work.

Right now, a pyramid of pipes and a pile of gravel wait on the side of that street where Michael Alexander lives, suggesting that for the first time in the three decades that he’s lived there, the sewer problem might be fixed.

What’s your favorite thing about Alabama?

That's the question we put to those at our recent News and Brews community pop-ups at Hop City and Saturn in Birmingham.

Q&A: A former New Orleans police chief says it’s time the U.S. changes its marijuana policy

Ronal Serpas is one of 32 law enforcement leaders who signed a letter sent to President Biden in support of moving marijuana to a Schedule III drug.

How food stamps could play a key role in fixing Jackson’s broken water system

JXN Water's affordability plan aims to raise much-needed revenue while offering discounts to customers in need, but it is currently tied up in court.

Alabama mine cited for federal safety violations since home explosion led to grandfather’s death, grandson’s injuries

Following a home explosion that killed one and critically injured another, residents want to know more about the mine under their community. So far, their questions have largely gone unanswered.

Crawfish prices are finally dropping, but farmers and fishers are still struggling

Last year’s devastating drought in Louisiana killed off large crops of crawfish, leading to a tough season for farmers, fishers and seafood lovers.

Lawmakers consider medical cannabis revamp

It’s been three years since Alabama lawmakers passed legislation establishing a system to govern medical cannabis in the state, yet not one prescription for the drug has been filled. The rollout has been delayed by lawsuits and conflict over the licensing process.