Corruption and the Economy

Over the last several years, Birmingham and Jefferson County have experienced a tsunami of political corruption. From the HealthSouth accounting scandal to the convictions of several former county commissioners. And, of course, next month Birmingham Mayor Larry Langford goes on trial in a 101-count federal bribery and conspiracy case. Les Lovoy reports on the toll political corruption takes on the our local economy and what the local business community people are plan to do about it.

Even before Since Mayor Langford’s indictment there were whispers. But since the indictment those whispers have turned into cries. A cloud of suspicion shadows every contract he proposes, every project he champions. Even those with no obvious hints of impropriety.

(Langford)”After 16 years of conversation, he said, she said, back and forth, we now have the opportunity this morning to make a 16 year old talked about dream a reality, and that is to release the funding to get the architects and the ball rolling for the dome stadium.”

“It’s inconceivable that there was the kind of support for the business community of Larry Langford.”

Jay Grinney is president and chief executive officer for HealthSouth Corporation, the rehabilitation giant that was itself the subject of a 3-billion dollar accounting fraud. Grinney was brought in to clean up the company and rehabilitate its image. And he’s a high profile figure leading the charge to clean up the county, starting with the mayor.

“He bankrupted Visionland, he created these huge problems that are on the verge of bankrupting the county, the indictments. It’s inconceivable, and we as a business community have to come together and say that kind of leadership is detrimental to every single person who lives in this community.”

University of Connecticut economist Steve Lanza is with the Economics Department at the University of Connecticut. He’s studiesd the affects of political political corruption on a community’s economy. He found when a business is considering moving to a new community, it’s much more concerned about corruption than high taxes. Specifically, among the negative factors of job growth in a community, the effect of corruption was 30% greater than taxes.

But Lanza admits, those numbers probably don’t accurately capture the full affect of public corruption. Statistics are extremely hard to come by for one obvious reason.

“The parties to the activities are trying to keep it a secret.”

Plus, Lanza says, just because there aren’t many convictions in any one community doesn’t mean it’s squeaky clean. He says researchers also have a challenge when tying conviction rates with a slumping economy because…

“That can depend on the kinds of resources that governments put into these states to try to root out and investigate corruption, and it may be the case that might look clean, might have few convictions, might be because the state’s so corrupt, they don’t bother trying to prosecute anyone.”

There may not be hard numbers, but folks who are trying to promote move Birmingham and Jefferson County to outside businesses say they know, for a fact, that the climate of corruption takes a toll on the local economy.

“I’ve had companies say, ‘we’re just not going into that environment.'”

Richard Findley, chairs the Birmingham-based Southern High Speed Commission. He meets with representatives from other states, who support a high-speed rail system, which would run through Birmingham, as well as several other cities throughout the South.

“It’s just retarded our efforts across the board, and it’s a shame because we’re strategically located for economic growth and development, and we can’t pull the trigger on any projects because of all the uncertainty associated with all of the corruption that’s going on.”

Some folks in Birmingham and Jefferson County are fed up with hearing about the corruption. Samford University professor of ethics John Knapp says the effectiveness of government is hampered greatly when residents don’t trust their elected officials.

“When people don’t assign good motives to public officials for the decisions that they make. When people question whether decisions are being made in the best interest of themselves and their families. Government becomes less effective because government officials no longer get the benefit of the doubt. They have to explain everything that they do to people who are very skeptical.”

Outside the county courthouse, Jefferson County employees and their families protest recent layoffs. Michelle Green told al.com that her mother was laid off.

“The reason I’m out here is I just think there’s a better way to solve this problem. I think the corruption in Jefferson County has gone way too far and it’s time we stand up and do something about it.”

Samford professor John Knapp says there are things citizens and business leaders can do to take to help reduce political corruption. Knapp lived in Atlanta in the early nineties when, he says, the school board was corrupt and inept.

“And, so the metro Chamber of Commerce in Atlanta actually organized an effort and funded it to recruit good candidates for the school and put more competent, more trustworthy people in those offices. And, they were successful.”

HealthSouth’s Jay Grinney says there’s a growing consensus the old way of doing business is no longer acceptable. And, he and other city and county business leaders are on a mission to work through the Birmingham Business Alliance to insist on integrity, transparency and quality in our elected officials.

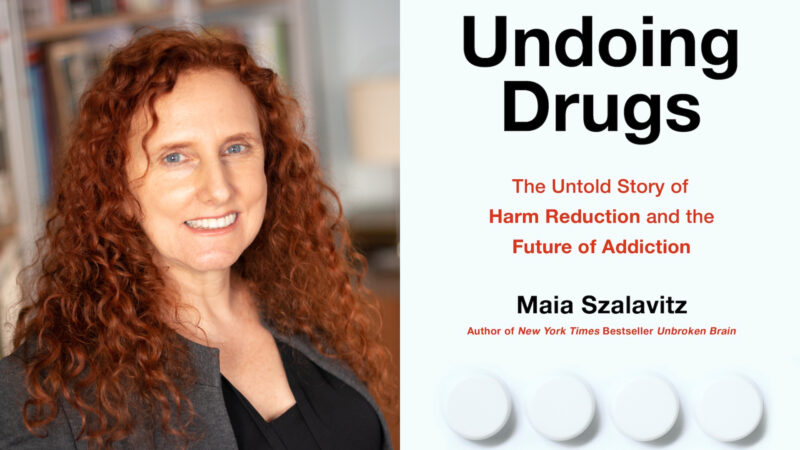

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What’s your favorite thing about Alabama?

That's the question we put to those at our recent News and Brews community pop-ups at Hop City and Saturn in Birmingham.

Q&A: A former New Orleans police chief says it’s time the U.S. changes its marijuana policy

Ronal Serpas is one of 32 law enforcement leaders who signed a letter sent to President Biden in support of moving marijuana to a Schedule III drug.