1 reason people don’t evacuate for hurricanes? Rising costs, and they’re getting pricier

A mangled tree blocks covers part of the street in front of a house in New Orleans' Carrollton neighborhood as Hurricane Francine hit the city with high winds and flooding rain on Thursday, Sept. 12, 2024.

Destructive hurricanes have affected millions of Americans this season — from Milton across Florida to Helene’s devastation in North Carolina. They’ve also shown the importance of evacuating.

Three factors often decide whether someone will leave their home because of a storm — if there’s a mandatory evacuation order, their experience with the last evacuation order and finally, the cost of leaving.

But what about residents on the outskirts of a bad storm? Or those in the direct path of a forecasted lighter, but still destructive, hurricane with no mandatory evacuation order?

While the safer route would still be to leave, fleeing a hurricane can be expensive. And it’s only getting pricier.

Evacuation costs — from meals to gas to hotel rooms — used to average around $300, economists say, but they’ve ballooned into the thousands in recent years. That could lead to more people gambling on hunkering down during a storm rather than accepting the cost of leaving.

The luxury of evacuating

In some ways, Nick Aucoin was lucky — at least as lucky as you can get with a hurricane forecasted to hit New Orleans, his hometown, directly.

Hurricane Francine made landfall last month as a Category 2 hurricane in southeast Louisiana before moving up to the Crescent City. No evacuation order told him to leave, but Aucoin has a newborn baby and was worried it could take days, or longer, for Entergy New Orleans to restore power if it went out.

So, he picked go.

That choice meant budgeting for gas, full meals and lodging. But Aucoin was still on paternity leave, so leaving didn’t mean lost wages like it can for many workers. And while parts of the Louisiana Bayou were without power for five days, most of New Orleans got electricity back much sooner. Aucoin’s home never lost power and he returned after just two days away.

Ultimately, the evacuation cost him about $500 — cheap by today’s evacuation standards and something he’s also lucky enough to budget for while knowing that’s not true for everyone.

“Evacuating is sort of a luxury,” Aucoin said, “I’m fortunate enough to partake in.”

Storms and evacuation costs are intensifying

Aucoin’s $500 expense may have been cheap by today’s standards, but 20 years ago, that would have been on the high end.

Back then, costs typically ranged from $350 to $550 in today’s dollars, according to economist Pallab Mozumder with Florida International University. Mozumder has found hurricanes in recent years, like Harvey, which devastated Houston, Texas, in 2017, have cost between $1,500 to $3,000 for evacuations.

Mozumder says one reason for the hike comes from the rapid strengthening of hurricanes caused by warm waters. Hurricane Milton, for instance, went from a tropical storm to a Category 5 hurricane in less than a day. These fast-strengthening storms can catch people off guard, leading to late evacuations, jammed-up roads, packed hotels and jumping prices.

“We have some anti-price gouging laws in Florida,” Mozumder said. “But in reality, you’ll see those things causing your evacuation expenses [to] go up.”

While climate change has not led to more storms each year, it has made hurricanes more intense, which can lead to more destruction and further disruption to supply chains. It can also drive evacuees further away from home for longer, raising expenses even higher.

FEMA can cover some of those evacuation costs, but that’s often not done until after a major disaster declaration — which typically happens after the storm has already passed — so there’s no guarantee of the kind of aid that will come after evacuating.

To prevent residents from staying and risking their lives to avoid travel expenses they can’t afford, Mozumder believes there should be state or federal programs that help cover the cost of low-income evacuees.

“All of the sudden, in a very short notice, you’re asking them to move and go away for a few days,” Mozumder said. “This is not their fault.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

GM to retreat from robotaxis and stop funding its Cruise autonomous vehicle unit

The automaker will focus on development of partially automated driver-assist systems for personal vehicles like its Super Cruise, which allows drivers to take their hands off the steering wheel.

Bankruptcy judge rejects The Onion’s bid for Infowars

The bidder that lost last month's auction of conspiracy theorist Alex Jones' assets had complained that the process was rigged and "fatally flawed."

Monarch butterflies will get federal protections as a threatened species

U.S. officials decided to extend protections to monarch butterflies after warnings from environmentalists that populations are shrinking and the beloved pollinator may not survive climate change.

Kroger and Albertsons grocery megamerger halted by two courts

Two rulings — in federal and state courts — make it increasingly likely that Kroger might abandon its $24.6 billion plan to buy Albertsons. The merger aimed to combine two of America's largest supermarket chains.

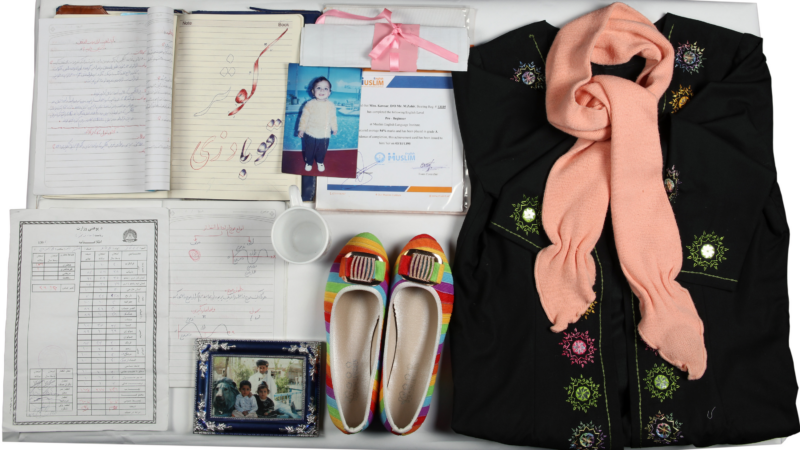

An Afghan museum, that buried its artifacts after Taliban takeover, is reborn online

The Afghanistan Memory Home Museum shares details and belongings from those who've died in conflict. It shut its doors when the Taliban took power, buried much of its collection — but has now reemerged.

Black Friday sends Taylor Swift back to the top of the charts

Stephen Thompson looks at the biggest songs and albums of the week, and digs into the stories and trends beyond the Top 10.