Bleached Creek Highlights ADEM Shortfalls, Say Critics

Alabama has some of the most ecologically rich waters in the world. But the agency tasked with monitoring them gets less funding per capita than that of any other state, according to a study by the Environment Council of States. Some complain the Alabama Department of Environmental Management (ADEM) is not doing its job. One recent example that conservationists cite is Buck Creek in unincorporated Saginaw, near Alabaster, Alabama.

David Butler of Cahaba Riverkeeper, an environmental watchdog group, is there taking water samples and measurements. There’s a chemical smell, and the creek bed is almost white.

“I would challenge you to find anything living in the water here,” says Butler.

He’s been testing the creek, and so has ADEM. The pH levels have come back similar to those of household cleaning products, and there was no visible life downstream of the pollution’s source: a nearby Carmeuse Lime and Stone processing plant. It’s unclear when the contamination began, but Butler filed a complaint with ADEM 14 months ago.

“We discovered it last year in June,” he says. “There’s still no resolution to it. Even with this ongoing damage that you see here, the state found it appropriate to go ahead and issue a fine without really looking at the impact.”

Carmeuse is a billion-dollar multinational. ADEM fined the company $32,000.

For its part, Carmeuse has paid the fine, and a spokesman says in a written statement, “after becoming aware that uncontrolled drainage was occurring to Buck Creek, Carmeuse immediately began an investigation to identify the source of that drainage. Initially, an area of surface erosion from a waste lime storage area was identified as the likely source. Further investigations conducted by Carmeuse also identified several areas impacted by water infiltration along the embankment of a reclaimed quarry pit … [We] began a hydrogeologic investigation to understand the cause of the water infiltration.”

Butler thinks the fine ADEM imposed is too low.

“When you have a company that has the resources to fight the state, there’s just not going to be significant penalties,” he says. “It discourages the companies that do do the right thing from spending the extra money to make sure that they’re in compliance with the law. Because if you break the law, you get a slap on the wrist.”

An ADEM spokeswoman declined to discuss Buck Creek. She did point me to a recent report outlining the agency’s funding challenges. It warns of potential cuts to basic functions like monitoring, testing, and inspection.

“What do we expect?” asks Pat Byington, who was on the state commission that oversees the agency. “ADEM used to get funding at a level of about five to six million dollars a year. In the last couple years, it’s virtually been zero.”

Now the agency relies heavily on permit fees paid by businesses and on federal EPA dollars. But EPA money is unpredictable. ADEM has increased its permit fees to make up for some of the losses. Byington, though, worries that sets up a system where the companies being regulated financially support the regulators:

“They’ve been raising more and more monies on the people they’re supposed to be watching – they’re the ones paying the freight.”

After decades of working on environmental issues across the state, Byington is not optimistic about ADEM’s funding outlook. He says Buck Creek is just one recent example of why. But he’s not questioning motives at Alabama’s regulatory agency.

“The people at ADEM, I know, care about the environment,” he says. But, “One thing we all know is that ADEM is terribly underfunded. And it’s just like not having cops on the street.”

Environmental advocates want voters to demand more state funding for ADEM, so staff can do the work, and so there’s more accountability to taxpayers.

In the meantime, Buck Creek is still polluted, even as it flows through a popular wading spot on its way to the Cahaba River.

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

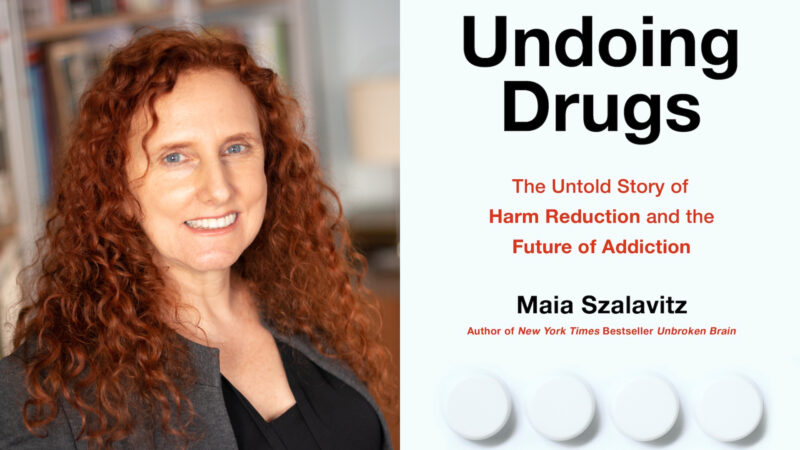

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.