Becky Anthony: Life With An Incarcerated Son

When a loved one is incarcerated, it can have a profound impact on their family members on the outside.

These families are lifelines to the inmate. From sending money to traveling long distances to visit the inmates, it’s work to provide that kind of financial and emotional care.

We explore those challenges as part of WBHM’s continued coverage of Alabama’s prison system. WBHM’s Sarah Delia has the story of one mother who has made countless sacrifices to keep her family afloat in order to support her incarcerated son.

Click here to listen to the story.

In 2013, when Becky Anthony learned that her son was sentenced to five years in Bibb County Correctional facility, she yearned to talk to other families going through a similar experience. But she had never heard of a support group in her community.

“You know we’ve got support groups for everything,” she said. “Drug support, alcohol, family life support, but no support group for family members incarcerated.”

So Becky, stressed, tired, and looking for a community to lean on, decided to take matters into her own hands by putting an ad in the local paper. The ad ran but she never got a phone call or email.

“It’s a shame,” she said. “I can’t be the only one going through this. I know I’m not.”

Sitting on a couch in her home outside of Jasper, Alabama, Becky’s hands are clasped tightly. She pauses frequently for cigarette breaks. She glances at the walls, decorated with pictures of her family.

All three of her children are grown, her two daughters both live on their own with careers and families.

But her 25-year-old son is a different case. She asked that he not be named for this story. He’s had a drug problem since the age of 12. That addiction led him to burglarize homes to support his habit and he landed in prison.

“He had opportunity and break after break. We knew that it would probably come to this, but it was nothing that I was prepared for,” she said. “We raised our kids the same way. One went in one direction one went in another, but they were both raised the same way.”

Becky, who’s 47, thought her life would be different. But on top of working full time, she’s the caretaker for her ex-husband who recently moved back in after having a stroke. And this house is new, because her family home that stood here previously burned to the ground in an electrical fire in 2011. Adding to all that, she has custody of her three-year-old grandson, Bentley, while his dad is in prison. It limits Becky’s options.

“I thought about going back to school. I had the opportunity to get transferred to another state, but couldn’t do it because I have Bentley now,” she said. “Just traveling, enjoying life. It’s not all bad. I’ve got Bentley and he’s wonderful. I’m very thankful to have that responsibility right now.”

The house is a playground for Bentley. There are toys, a swimming pool, movies, and lots of attention from family. He seems to be a happy kid, and Becky lights up when he smiles.

When she can, Becky and Bentley make the almost two-hour drive to prison to visit his dad. But at the time of this interview, she was told she wasn’t allowed to speak to him because he was on lock down. Without in-person visits or phone calls, the’re left to communicate through letters.

Her son writes about his cellmates, asks how the family is doing. He shares his hopes and fears. And every letter, she says, includes questions about Bentley.

Becky says the day her son went to prison, it felt like her entire family went to prison, so her hope for her future is simple.

“To enjoy life a little bit and laugh and really feel the laughter. You can put a smile on your face and go about your day-to-day activities and a lot people looking at you might not think there was anything wrong. But to really enjoy life. To breathe. Because that seems like that’s one of the hardest things to do lately is to breathe.”

Her son’s release date is in 2018. She says she believes some good can come out of the pain her family has endured when he’s reunited with his son and they start a new life together. Then she says, she’ll be able to breathe.

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

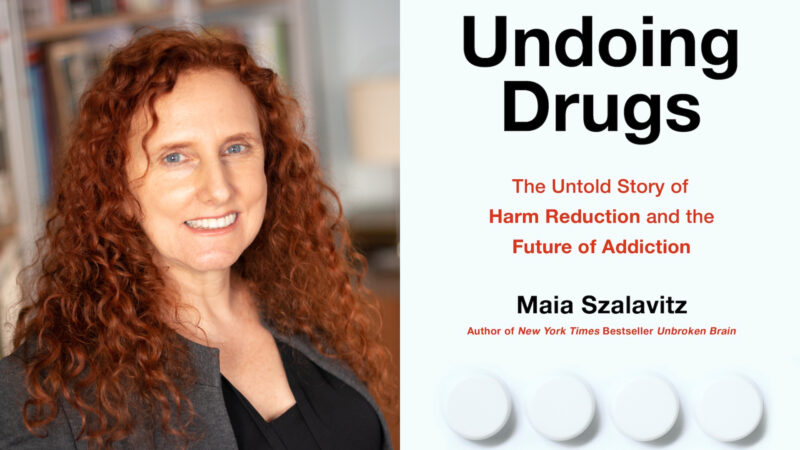

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.